TRAUMA IS NOT YOUR FAULT. [PERIOD]

Trauma is not your fault. [period]

Take all the time you need for that to sink in.

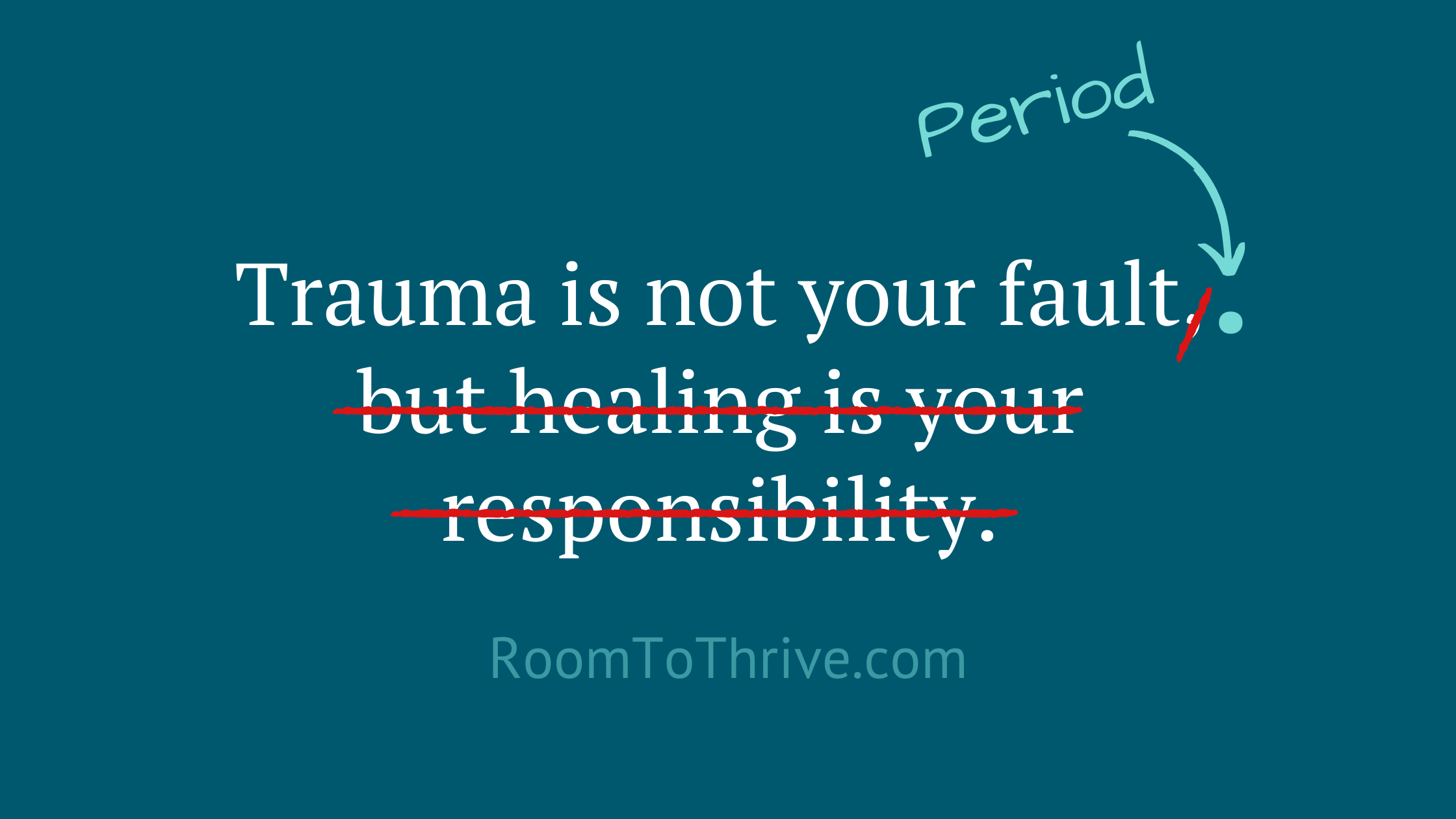

Over the past several years, the following phrase/meme has made its rounds.

“Trauma is not your fault, but healing is your responsibility.”

There’s something about it that never sat well with me, and last night I jotted down a few of my thoughts. I’d love to know what you think.

The dismissive “but…”

Folks who’ve experienced trauma are familiar with the dismissive “but” that often follows, “trauma is not your fault, but…”

“…but I should have fought back.”

“…but I shouldn’t have gone to that party.”

“…but I should have seen the red flags.”

“…but what were you wearing?”

“…but healing is your responsibility.”

This last “but” appears well-intentioned while still carrying a similar weight of individual responsibility for a process that is rarely possible on one’s own.

It has that familiar individualist ring to it that has folks grabbing for their bootstraps while standing alone in their suffering.

Trauma is not your fault. [full stop]

*long pause*

I can’t begin to describe the importance of that full stop or the healing potential contained within the space that follows.

As soon as we add a “but…” we knock some of the air out of this realization. It feels like a punch in the gut or that sinking feeling that accompanies “…but I should be over it by now.”

While the idea of personal responsibility comes with a bit of hope, it also comes with pressure. In my experience, this burden outweighs the hope for many trauma survivors.

When pressure outweighs hope, it’s no longer empowering.

Embodied hope has the potential to be a resource for a survivor’s nervous system. Pressure, on the other hand, comes with the risk of overwhelming one’s nervous system or keeping it stuck in freeze/collapse physiology.

Trauma is already an isolated place, and making healing “your” responsibility remains limited to one person. Trauma already feels like a personal failing or weakness, and “your responsibility” adds one more shortcoming to your list, that of not yet healing.

Something happens when we add a well-placed full stop at the end of, “Trauma is not your fault [full stop]”

This pause creates some much-needed space.

A space that is frequently punctuated with a sigh of relief. It’s a place without a dismissive “but…” or added pressure of any kind. This pause may be the first time a survivor feels heard and understood.

It’s important to hang out here for a while.

There’s a great deal of healing potential here if we’re willing to sit with survivors without giving in to our impulse to fix it, solve it, make it go away, or in this example, ascribe responsibility.

To be clear, I believe in survivors’ capacity for healing, which is why I’m passionate about helping to create a supportive and empowering context. I’m not convinced that saying, “…but you’re responsible for your healing” creates a supportive context.

We don’t heal alone.

We’re social mammals who require the presence of another nervous system for critical developmental tasks, and our ability to co-regulate is vital for healing trauma.

Humans need to feel safe, strong and connected, and we’d be well-served to keep these in mind as we search for what to say next.

So, what do we say to a trauma survivor after they’ve had the space and time to acknowledge trauma is not their fault?

Here are a few possibilities:

“…and healing is possible.”

“…and you have the capacity to heal within safe and supportive relationships.”

“…and I’m committed to being here with you as a resource for your nervous system.”

What would you add?

Again, I assume the original idea is offered with the best intention. However, language is powerful and “but” is often dismissive and may do more to reinforce trauma physiology than to create a context for healing.

I also recognize that each person’s experience is unique, and the original phrase may be helpful for some folks. If that’s the case for you, I acknowledge your experience is valid and I celebrate what works for you!

If, however, you’ve felt uneasy when you encountered the original phrase, I’d love to hear your reaction to my thoughts above.

“You’re removing personal responsibility from trauma survivors.”

After sharing this on my Facebook page, several folks expressed concern that I was attempting to remove all personal responsibility or agency from trauma survivors. I appreciate this concern and went on to clarify with the following.

I appreciate your perspective, and I recognize there are many paths that lead to healing. What works for some may not work as well for others.

What’s the difference between, “It’s your responsibility to heal” and “We don’t heal alone?”

I think some of the distinction between “it’s your responsibility to heal” and “we don’t heal alone” is the first assumes some privilege and access to necessary support, while the second acknowledges that healing is not an individual effort.

“Your responsibility” may also overlook the role the autonomic nervous system plays in trauma. Many of the physiological responses inside of trauma happen without our consent and without our direct ability to change or control. The role of our autonomic nervous system does not imply that we are powerless to impact our healing; rather, it points to the importance of context in the healing process.

“Your responsibility” also comes across to many survivors as “why aren’t you trying harder,” or implies survivors have chosen to remain stuck in trauma. These sentiments, while well-meaning, don’t fully grasp how trauma works and are often fueled by the toxic positivity permeating our society.

This isn’t about “playing the victim.”

What I’m suggesting is not “playing the victim” or “looking for an excuse to remain stuck.” In fact, it’s quite the opposite. Telling someone who is in freeze/collapse physiology that they are responsible for their own healing can make a dark and lonely place even more isolating. In many ways, this approach reinforces the experience of powerlessness.

Unfortunately, it’s all too common to mistake a survival instinct for a moral failing.

A more obvious example might be telling someone not to be afraid of [x]. A person’s fight/flight response will likely not respond to these kinds of commands. It’s not that anyone wants to remain scared, it’s that our nervous system needs to feel safe in order to exit survival physiology. Sometimes, we’re capable of doing what’s necessary to feel safe, and sometimes we’re not.

It’s important to recognize our survival physiology.

We often do more harm than healing when we overlook the fact that we’re social mammals with nervous systems that are primarily focused on survival. Our thoughts, beliefs and judgments are valuable in many areas of life, but they almost always take a back seat to our survival instincts.

When we recognize how much of trauma exists within our survival physiology (not our cognitive constructs), we begin to understand the difference between strategies that address the needs of the nervous system and approaches built on socially-constructed narratives. Supporting survivors’ physiological need for safety, power and connection can create a context for healing. Expecting survivors to live up to the social construct of rugged individualism will likely not be helpful for many survivors.

I don’t pretend to have all the answers, and I’m likely wrong about some of what I’ve presented above. I’ve already learned so much from the responses to my original post, and I look forward to learning more. At the end of the day, I’m just grateful we’re having this important conversation about trauma.

If this blog post resonated with you, I would love to stay in touch. Feel free to include your first name and email below and choose which resources you’re interested in learning more about.

Here’s to continued healing!

-Brian Peck, LCSW

This post originally appeared on Room to Thrive’s Facebook page, written by Brian Peck, LCSW. It has been republished on The Mighty and Yahoo

Brian Peck, LCSW, is a licensed clinical social worker specializing in religious trauma and supporting folks with a history of adverse religious experiences. In addition to supporting trauma survivors’ recovery, Brian is passionate about reducing the stigma attached to non-believers, especially those who have exited high-demand religious communities.